Sweet Emily

(Leon Russell)

From the Leon Russell album Leon Russell and the Shelter People

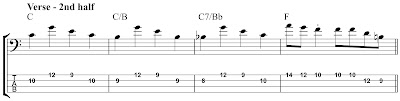

“Sweet

Emily” from Leon Russell and the Shelter

People is a light, medium-tempo song with a nice, laid back feel. It is in

a classic AABA form (more about AABA below)—the verses are the A sections, the

bridge is the B. Radle plays almost the exact same thing each time the A

section comes around. The bridge only appears twice. Radle plays a similar line

in each bridge, though the bass line in the second bridge is slightly

embellished.

AABA

This song

gives us a good opportunity to talk about what is likely the most common form

in all of popular music. The AABA form was extremely prevalent in popular music

before around 1955. Show tunes often utilized the AABA form (and still do), as

did much of the music that came out of Tin Pan Alley. Consequently, most jazz

standards are AABA, as they are often songs from musicals and Tin Pan Alley.

AABA songs do not have a chorus. The A section is often the catchy or memorable

part of the song, and will usually be the part that states the title. Each A

section will use the same melody and chord progression, but will have different

lyrics. The B section, or bridge, is used as contrast and to build tension before

a return to A.

AABA

forms are usually 36 measures long, each individual section lasting 8 measures.

In a slow tempo, a band or artist may just go through the form once and end the

song. In faster tempos, some or all of the form may be repeated. In “Sweet

Emily,” Russell moves through the AABA form once (mm. 5-29), then repeats the

BA (mm. 30-45), which is a very common method of extending the form. For some

other examples of AABA songs in the pre-rock & roll era, listen to

“Somewhere Over the Rainbow” as recorded by Judy Garland, “All or Nothing” as

recorded by Frank Sinatra, and “Hey Good Lookin’” by Hank Williams.

In 1955,

rhythm & blues music crossed over into the mainstream popular music market

and rock & roll was born. Of course, the sounds of rock & roll existed

before 1955, but it wasn’t its own genre—it was just a small segment of rhythm

& blues. With the rock & roll boom of the mid-to-late ‘50s, the AABA

form did not fade away, but it became only one of several prominent forms.

Early rock & roll relied heavily on the 12-bar blues. How many Chuck Berry

and Little Richard songs can you name that utilize the 12-bar blues? It’s

probably a shorter list to name the ones that don’t.

As rock

& roll developed into the 1960s, having a catchy chorus became increasingly

important, so verse-chorus songs became more of the norm. But you can still

find plenty of AABA forms throughout the 1960s and ‘70s. The Beatles used the

form often—“Hey Jude,” “A Hard Day’s Night,” “Something,” and “Yesterday” are

AABA, to name just a few. Led Zeppelin made frequent use of what is called

compound AABA, meaning that each A and B section is made up of multiple smaller

sections. “Whole Lotta Love” is a

good example of that.

Pay

attention to the form of the songs you’re playing or listening to. Knowing

where you are in a song is important. Understanding the form can help you learn

songs faster, can keep you from getting lost (in the music, not in the world),

and will increase general understanding of music. And the more we understand

music, the more fun we can have with it.